Just shy of two years after steering Sweden’s accession into NATO, Tobias Billström has taken a turn into the private sector. The country’s former foreign minister is the new director of strategy and government affairs for Nordic Air Defence (NAD), the Stockholm-based startup building drone interceptor technology.

Billström said his move to NAD underscores what he believes will be the next chapter for Sweden in defence. In short, NATO membership will open doors for NAD as well as other suppliers to develop and build more defence tech, and to sell that beyond the Swedish market.

“Joining NATO means that companies in Sweden will be able to act within the framework of Sweden being an ally — a full military ally,” Billström told Resilience Media on a video call.

Sweden joining NATO, and Billström joining NAD, are both unfolding at a key geopolitical moment in Western Europe.

Countries see Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as both a specific sovereignty threat in one country as well as an existential crisis for Europe overall. And it points not just to who and what the adversary is, but also how warfare is evolving. All of this is spurring increased activity in defence and defence tech across Europe and beyond.

Yet the developments also come at what is still a pretty nascent moment for Sweden’s defence industry.

One of the biggest names in tech in the country, Spotify founder Daniel Ek, is heavily investing in military technology. But that focus has largely been trained on funding Germany-based Helsing – currently the largest defence-tech startup in Europe with a €13 billion+ valuation.

The Swedish ecosystem is at a very different stage. NAD’s modest funding – €4.4 million in pre-seed investment, led by Inflection and concluded in July 2025 (per PitchBook data) – is actually the largest publicly disclosed raise in any Swedish defence-technology startup to date.

Billström is nonetheless bullish about his country’s innovation edge, arguing that its technical capabilities were a major attraction to NATO.

“[NATO allies] know that we bring well-equipped, well-trained troops,” he said. “We have capabilities in all five domains of NATO — land, sea, air, cyber, space. We even have our own space base, the Esrange, high up north, which means that we can launch satellites from our own territory.”

Sweden’s NATO membership, he added, will give NAD access to new channels to market that it didn’t have previously, including collaborations with DIANA, NATO’s accelerator for dual-use technologies, and new testbeds.

“[This] is one of the reasons why we joined in the first place,” he added. “Being part of this vast security network enables Sweden to become a security provider.”

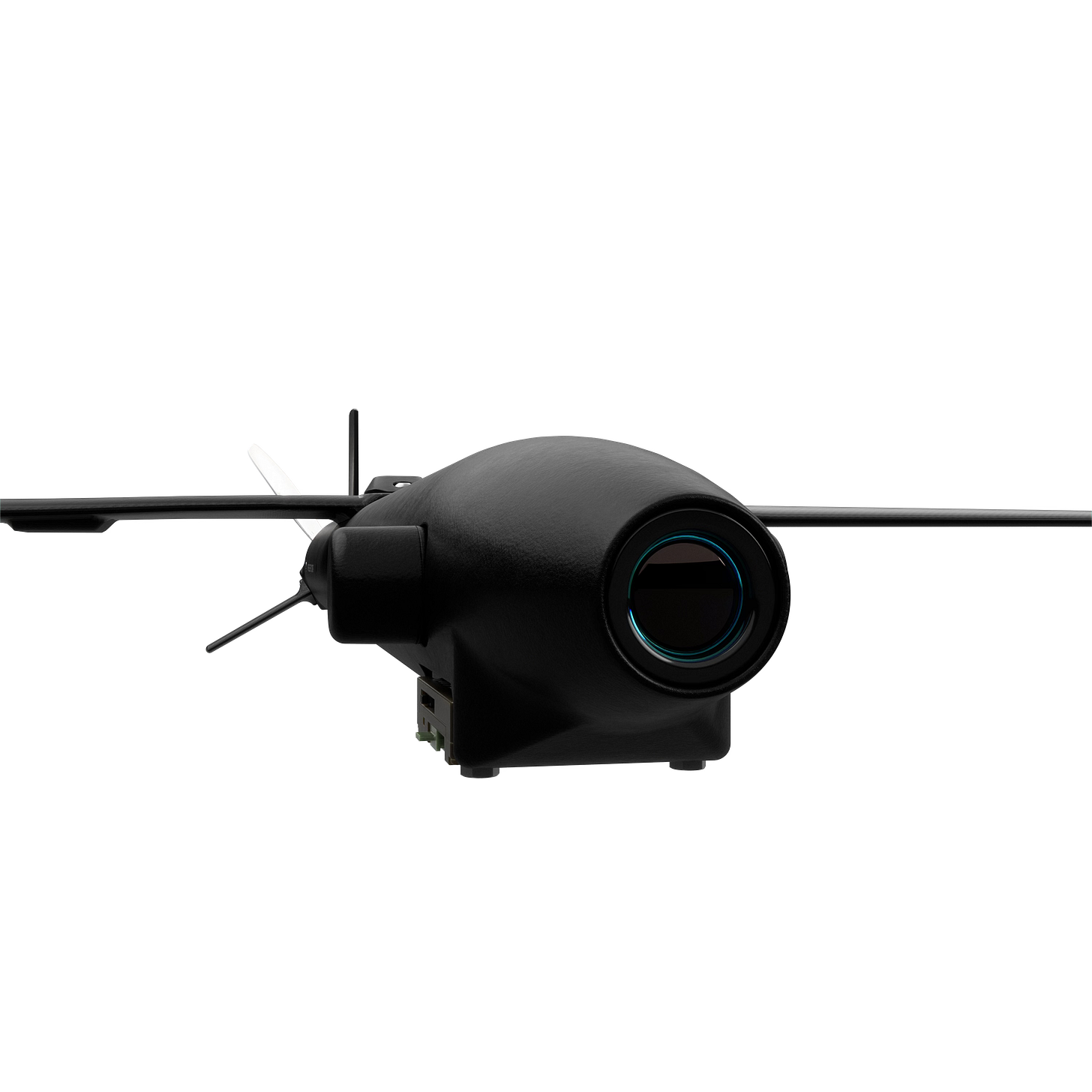

NAD’s flagship security product is the Kreuger 100XR, a foot-long, missile-shaped drone interceptor with an optional warhead. The system’s intercept range is billed as more than 5km.

NAD has also developed an embedded AI that enables “fire-and-forget” operations with autonomous detection, classification, and tracking.

Other features include a thermal infrared seeker, continuous ground control in radio frequency-stable environments, and a radio-silent autonomous mode.

Like many startups in the sector, NAD is focusing on interoperability, which gives smaller players a chance to both compete with larger primes and potentially collaborate with them.

NAD is ticking that box with “plug-and-play” integration, recently showcased in a collaboration with Volvo Defence. Together, the pair developed the Vipro, which mounts the Kreuger 100XR onto Volvo’s tactical trucks. Vipro is slated for operational introduction in 2026.

A key selling point for the Kreuger is its low production cost. NAD claims it is 10 times cheaper to produce per unit than conventional anti-drone interceptors and missiles. The startup credits the savings to replacing hardware in drone interceptors with software. Billström says the shift supports mass manufacturing in the EU.

“As we can see throughout the European Union at the moment, when it comes to defence procurement, you have two challenges,” Billström said. “One is the ability to scale up to produce in volume, and the second is that you have to produce things that are cost-efficient. These two are, of course, intertwined.”

Trial by political fire

Billström’s perspective on the market has been honed through a political career spanning more than two decades. Appointed Foreign Minister in 2022, he guided Sweden into NATO in March 2024. Following accession in March of that year, he said Sweden would stand for “fair burden-sharing,” with defence spending exceeding 2% of GDP for the year, “which should be considered a minimum level.” However, he resigned from the government that September.

Leading up to accession, Sweden’s path to NATO had been protracted and politically fraught. Objections from Turkey delayed accession for about two years from the 2022 application, primarily due to Ankara’s viewing Sweden as supportive of Kurdish separatists. President Recep Erdoğan used the negotiations as a bargaining chip, hinting that his approval would be conditional on the US selling Turkey F-16 fighter jets.

Hungary withheld support even longer, citing Stockholm’s criticisms of the country’s democratic backsliding. Analysts attributed the intransigence to its ties with Russia and attempts at power brokering. As with Turkey, they saw Hungary’s potential veto as a bargaining chip. Hungary, they argued, was pressuring the EU into releasing billions in funds that had been frozen due to corruption and rule-of-law concerns.

During the standoff, Billström said he saw “no reason” to negotiate with Hungary “at this point.” Yet he added that the two nations “can have a dialogue and continue to discuss questions.” A month later, Hungary approved Sweden’s accession.

Billström will bring lessons from these experiences to his new role at NAD. He counts knowledge of policy matters, complex negotiations, and “how the security networks function” among his expertise, and said that he wants to apply his skills at “all levels” of the business.

“The most important thing is to win contracts,” he noted. “The idea is to look to the Swedish market, but also beyond that, to both the European and perhaps potentially also the American market,” he added.

The Ukraine effect

Sweden also has firm sentiments about Europe’s current geopolitical climate, particularly in light of the threat from Russia. Asked whether NAD planned to sell directly or indirectly to Ukraine, his response was unequivocal. “Of course,” he said.

Billström’s attire reflects his words. On the lapel of his three-piece suit, he has pinned a badge with the flags of Sweden and Ukraine joined together. It’s an alliance that he insists his country still firmly supports.

“It’s very, very strong,” he said.

Polls back him up. A survey published this year by Gallup Nordic found that 75% of Swedes support Ukraine in the war against Russia.

“I don’t see either politically or in the public sphere any slacking or any diminishing trends taking place,” he said. “On the contrary, I think that what is going on right now shows that Sweden is willing to continue to support Ukraine, both from a NATO perspective, but of course, even more from an EU perspective.”

One benefit of the bond with Ukraine is the latter country’s experience with defence tech – “live” learnings that other international startups have also highlighted.

“Ukraine is paying a very, very heavy price for this in the violence and in the bloodshed, but we have to listen to what they are learning so that we can do things in a better way,” Billström said.

He links these lessons directly to NAD’s drone interceptor. The world has entered “a new phase of modern military warfare,” he said, exemplified by the widespread use of drones in Ukraine. “That’s something NATO and NATO allies have to take on board very seriously,” he said.

NAD also has a more immediate would-be customer: Sweden itself. After reaching defence investment of around 4% of GDP during the Cold War, funding had fallen to around 1% of GDP as recently as three years ago. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 then spurred an increase in the defence budget. The government plans to take spending to 2.8% of GDP next year.

Swedish politicians have also renewed their focus on defence innovation. In June, the government adopted a new Defence Industry Strategy, which focuses on deeper collaboration between the military and the technology industry. NAD welcomed the announcement.

“You need to have a closer collaboration between civilian and military authorities,” Billström said. “It’s also a question about rules and regulations,” he added. “And our company is very much involved in a dialogue with the procurement agencies, as well as those agencies and authorities responsible for the export of technology for dual use.”

Sweden’s entry to the NATO alliance ended more than two centuries of military non-alignment. Billström described it as “an historic step” and part of a “paradigm shift” in foreign policy. Yet he adds that life outside the alliance had positive effects on defence tech, too.

“The irony is that Sweden, being a non-military aligned country, forced us to become very good at what we’re doing,” he said. The Malmö native highlighted two domestic advantages: engineering excellence and industrial capacity.

“Those two factors together have brought us to the point where we are today,” he said. “I mean, how many other countries in the world who have 10 million inhabitants have been able to produce a jet fighter? Not many, historically.”

Billström believes his new employer is a part of that trajectory.

“NAD ties into this tradition of using innovation, using our industrial capacity, and using our ability in modern times — with startups — to do things which other countries may not be able to do.”