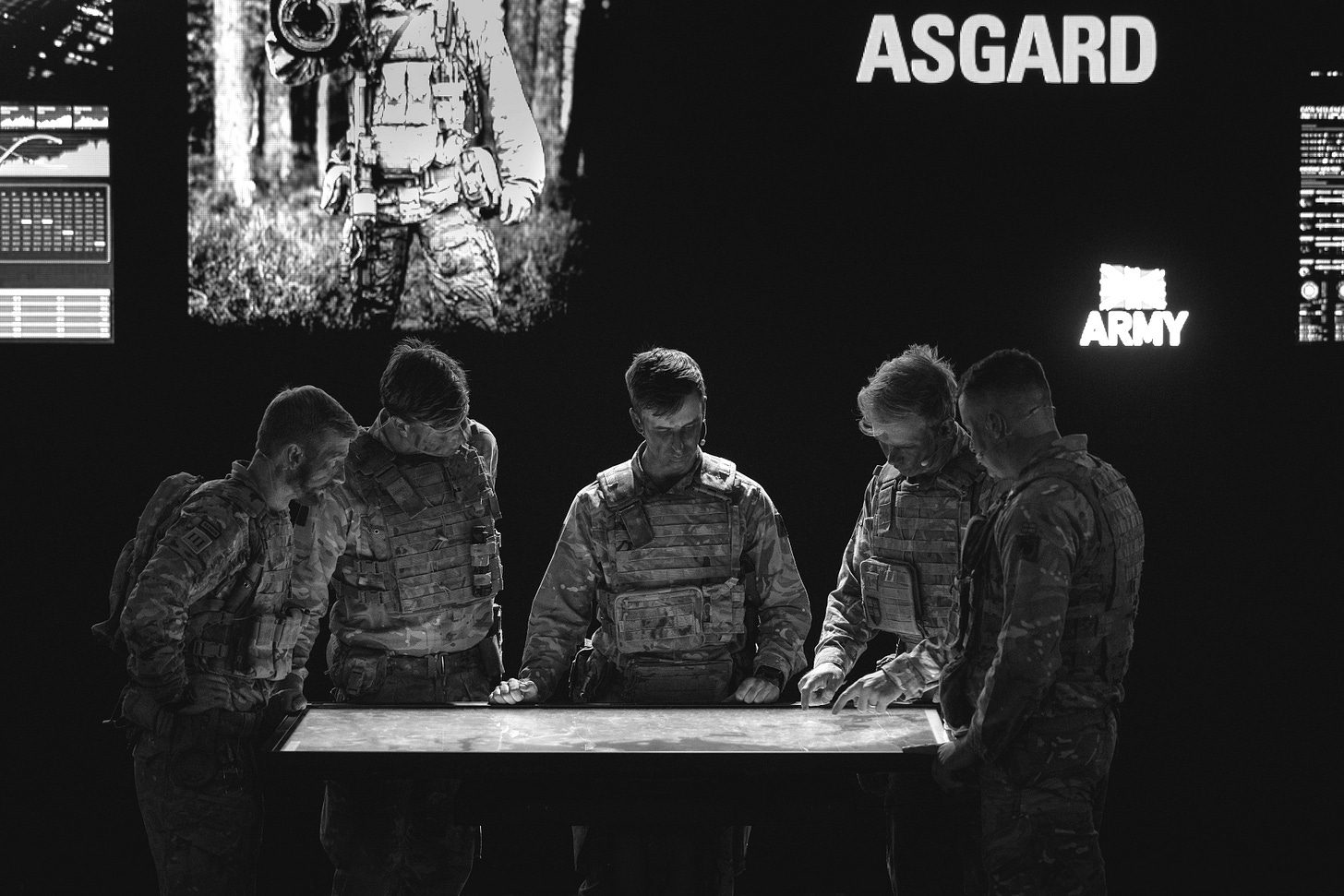

At a private event in Central London earlier this month, the British Army put on an impressive launch of Project ASGARD to show off its plans to provide enhanced, AI-based targeting and surveillance capabilities to its forces. The event was attended by the Chief of General Staff, General Sir Roly Walker, and leaders from across the British and NATO militaries, along with tech companies and startups involved in the project. It was fitting that General Roly was there as Project ASGARD is a response to his pledge to double and then triple the Army’s lethality by 2027 and 2030 respectively.

ASGARD’s digital targeting web will use the latest AI and autonomous tech to dramatically increase the speed and mass of a response to a Russian incursion, in particular into Estonia. An increase in lethality does not just mean more weapons, it can be achieved by better sensing, better coordination, faster decisions, and rapid deployment of the right weapons.

Most of the work on ASGARD, to date, has yet to enter the live field, and there will be a lot of questions over how state-of-the-art technologies will fit together with larger, legacy military hardware, but the MOD remains focused and said that it is putting more than £1 billion into further development of ASGARD as part of its strategy to improve the digital targeting web across the UK’s Armed Forces by 2027.

In a London Army barracks David Williams, the Army’s CTO, introduced the event by warning us that we are now preparing for the mainland to come under direct threat. He referenced Lord Robertson, in the UK’s Strategic Defence Review, saying ‘we are no longer safe,’ and this event was to unveil some of the Army’s first steps in response to this.

‘ASGARD provides the opportunity to flip our Forward Land Forces in Estonia from a strategic tripwire into a potent strategic asset, setting conditions for an unfair fight in the Alliance’s favour,’ he said, noting it is also an investment in economic growth and innovation for the UK.

The challenge set to ASGARD was to address an ‘urgent need to think and fight differently,’ Williams explained, to enable us to detect a potential enemy incursion into a NATO country, and to ‘find, strike, and blunt enemy manoeuvre.’

To achieve this, ASGARD focusses on three interventions: first, to enhance the voice and data communication at the edge; second, the introduction of the DART 250 One Way Effector, which can target enemy infrastructure three times further away than current UK land based deep fire rockets; and third, to accelerate the digital targeting capability.

Director of Army Futures, Major General Alex Turner, warned that when the war in Ukraine ends, Russia is expected to redeploy its battle-hardened and experienced soldiers along NATO’s border. ‘Doing nothing is not an option,’ he said.

Turner outlined the reality of a transparent battlefield in which speed and unpredictability, along with electronic warfare, will be essential. He focussed on the need to ‘see further and strike further’ for better tactical precision and targeting enemies ‘far beyond the horizon’ to be able to see where the enemy is and what it is doing — a concept known as ‘recce strike’ (short for reconnaissance strike). He also outlined a very automated future in which ‘it is unlikely that crewed systems will constitute more than 20% of the systems we take into the field.’

ASGARD is a capability described as unique to the British Army, and which is tailored to optimise recce strike. It is about ‘techcraft’, which the Army uses to describe the concept of ‘Technologist to Tactician,’ essential to creating an ‘unfair fight’ against adversaries, in its words.

To that end, ASGARD has brought together 27 defence tech companies with users from the Army to create a new ‘digital targeting network’ that, in theory, will enable troops to run a sequence of actions based on the principles of: ‘sense,’ ‘decide,’ and then attack with an ‘effector.’ The idea is for information to be moved between human decision makers at machine speed, compressing the targeting chain from hours or even days down to minutes or seconds, whilst still maintaining a ‘human in the loop.’

AI is at the heart of ASGARD, with the system designed to use AI to identify targets, manage the decision-making structure, and even recommend which weapon to use.

And at the demonstration, this was played out with some immersive flair. The attendees wore VR headsets to become part of a real-time simulation showing the interconnection between all the sensors in the field as a NATO battlegroup took on a Russian invasion of Estonia. In this scenario, every piece of hardware and every soldier is a sensor sending information back to the command centre to influence decisions and attack effectors. This was played out on a large map that zoomed in and out to show tanks, drones, satellites, and the green dotted connections between them.

Major General Mike Keating, the Chief of Staff of the HQ of NATO’s Allied Rapid Reaction Corps (ARRC), set the scene for how future iterations of ASGARD would help defend NATO.

He painted a picture of a near future in which the war in Ukraine has come to ‘a messy and inconclusive end,’ with Putin increasingly paranoid, his army angry and re-manned by ‘convicted murders and psychopaths, and the dregs of Russian society unable to bribe their way out of the draft.’ NATO Article 5 has been invoked after a series of apparently random incidents have escalated to some Russian Special Operations troops being captured near a military base in Estonia.

At this point in the demo, lights revealed soldiers in camouflage crouching in an imagined Estonian forest launching a drone, the video feed of the forest playing out on a screen in the room showing Russian troop movements. In the darkened room, real groups of soldiers then simulated an escalating military situation that culminated in attacks on Russian ground targets. The simulation demonstrated the way these teams were highly connected, with the various sensor and drone feeds operating seamlessly between them, and AI enhanced decision making allowing a very fast, real time response to the incursion.

General Keating explained that at this stage of escalation, ARRC has assembled a force of 75,000 British and Italian troops across Central Europe, ‘all connected together via the ASGARD digital kill-web, that ensures the seamless transfer of data between all parts of the Corps.’ All of this focusses in on the ‘Sense, Decide, Effect’ interface of ASGARD. He concludes the simulation by explaining that, ‘the power of ASGARD is that it allows organisations, and people from Corps to foxholes, to prioritise what we target…despite facing a tsunami of data overload.’

Anthony McGee, the director of Taskforce RAPSTONE, which oversees ASGARD, explained to the audience that RAPSTONE is the UK’s response to the lessons it has learned supporting the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

‘It is about how to organise ourselves and build partnerships that deliver modern technologies into the hands of soldiers at pace… it is focussed on the near-term and keeping a real emphasis on delivery,’ he said.

A defining feature of ASGARD, and of most interest to Resilience Media, was McGee’s clear statement that RAPSTONE wants to ‘reach out to companies that have not traditionally worked with Defence,’ but that may have solutions the Army needs.

To support this, he announced the launch of the British Army’s Challenge Set, which is now in the public domain. The hope is that the Army’s Challenge Book will encourage new, non-defence startups and tech companies to enter the Defence sector.

The many critics of defence procurement will also have been pleased to hear McGee say that the ‘challenges are framed around effects we aim to achieve, rather than prescribing specific equipment or services. We want UK industry to bring us the best solutions, unrestricted by preconceptions.’

The event then focussed on the 27 industry partners. Amongst them were familiar names, like Helsing, Rowden, and Anduril alongside companies like Oxford Dynamics, Intellium, SensusQ, and Mind Foundry.

Helsing showed a video of its Altra targeting software combined with its HX-2 AI-enabled drone being used to detect and strike a target at unprecedented speed. This is a core part of the ASGARD capability, and only one of only two technologies that has been deployed and demonstrated in the field, the other being the secure communication system developed by Rowden.

This reflected concerns amongst some of the companies, and from some of the military, that the speed of ASGARD’s deployment and scaling is far too slow, and that more traditional thinking elsewhere in the MOD is dampening the relatively extreme pace set by RAPSTONE and ASGARD.

One tech company in the ASGARD group said it was concerned that it had not yet visited Estonia to test its novel technology, despite equipping the UK’s 4 Brigade based in Estonia being a core purpose of the project. Others echoed concerns about a gap between the vision being presented and the reality on the ground, along with the funding required for the Army to realise the vision.

This was recognised by McGee, who acknowledged that the long term scaling of ASGARD will face challenges, such as those now being tackled in procurement reform. He appeared confident both in his understanding and recognition of these challenges, and his resolve to overcome them.

The vision of ASGARD is impressive, and the fact that the Army has focussed serious resource into the project is reassuring. The demonstrations were slick, compelling and communicated clearly how ASGARD could create a powerful integrated network of sensors and technology to identify and neutralise an enemy incursion into a NATO country.

The ability of the NATO ARRC to respond to an attack by Russia in hours and minutes rather than days or weeks, with mass drone attacks rather than only tanks and troops, underpins how it understands the role innovative tech will play in confronting an enemy that massively outnumbers it, and reflects real lessons from Ukraine.

There was a justified sense of excitement and achievement mixed with justified byt pragmatic concerns and frustration, especially from those most aware of the real threat we face on our Eastern Flank and the very short amount of time we have to be ready to confront it. ASGARD is a great initiative, approaching procurement and engagement with the tech sector well, and learning from Ukraine. Hopefully, it can be given not just the funding it needs, but also the independence to move at the speed needed in wartime innovation, without being held back by the structures and approaches of peacetime innovation.