The world of defence drones on about drones, but it’s for good reason. Unmanned aircraft have opened up a significant new front in how militaries engage with the enemy. In Ukraine, for example, on the offence, they are being used to gather information, deliver goods, or drop weapons. Typically priced at a fraction of the cost of more traditional equipment — prices can be as low as in the hundreds or thousands per device — drones proportionately cause immense damage.

But turned around, that same trend poses a large threat when it comes to defence. A new report from Dedrone — the air defence and data business Axon acquired last year in a deal that valued Dedrone at $500 million — outlines some of the ways that drone warfare is evolving and the challenges that presents in terms of detection and traction.

Yes, the report comes from a vested interest in the game — Dedrone, after all, makes tech to detect and track these unmanned vehicles. However, looking at how widely drones are getting used in major conflict zones today like Ukraine and Israel, their use is not going away soon. As a big defence conference kicks off this week in London, here are some of the top-line takeaways in the report:

The market is highly fragmented, and the number of “DIY” drones are growing.

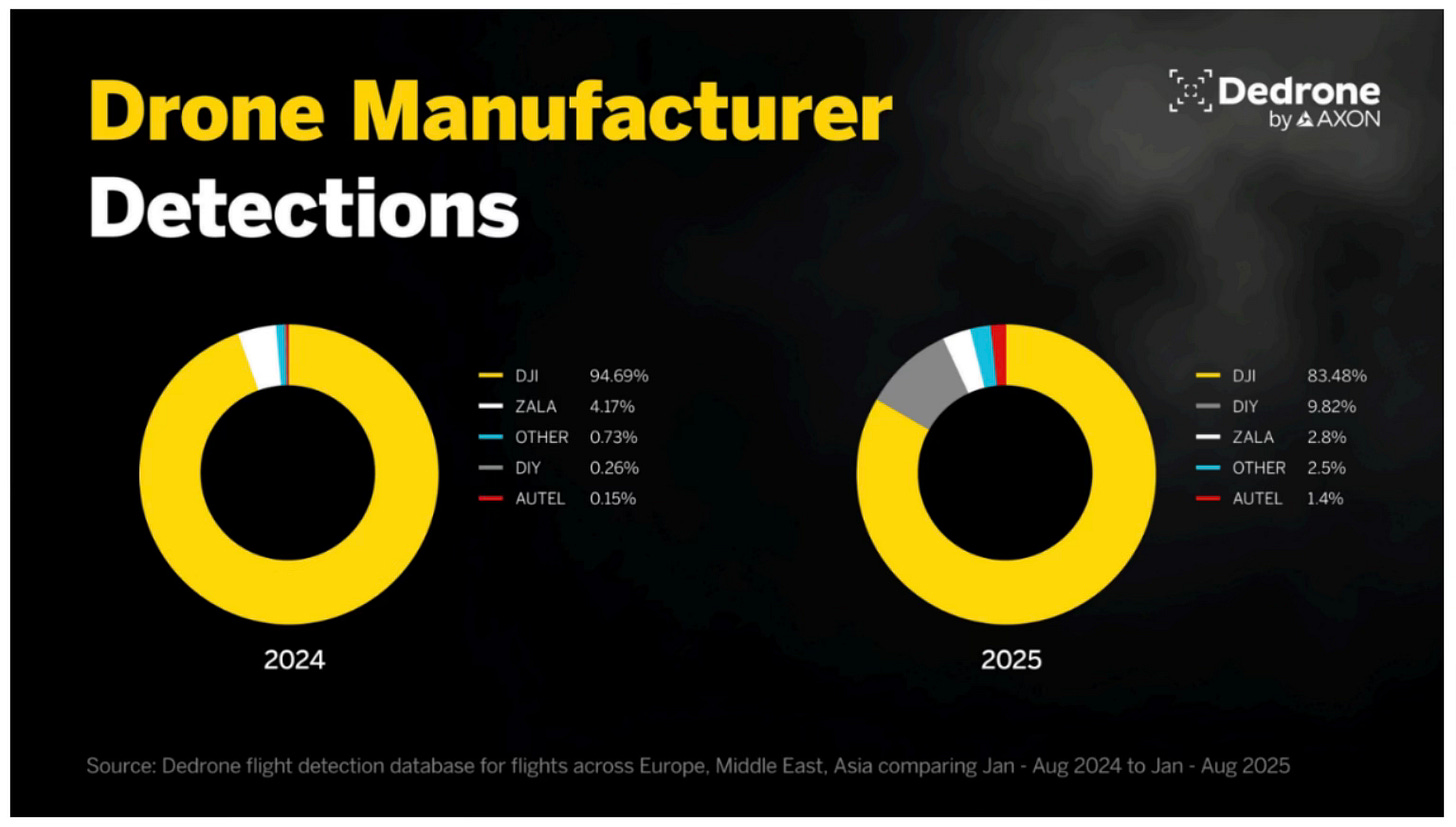

Chinese drone maker DJI, the biggest producer in the market for years now, continues to dominate among vendors, but its presence overall has actually declined. Data that Dedrone has collected across Europe, Middle East and Asia over the last year saw DJI’s share of the skies drop by more than 10 percentage points, from 94.7% to 83.4%. Russian maker ZALA also saw a decline from 4.2% to 2.8%, while another Chinese maker, Autel, saw its share go from nothing to 1.4%.

By far, the biggest growth came from DIY — drones assembled from components and powered through open-source software (Crazyswarm is one example). DIY drones accounted for 9.82% of drones in the sky in 2025, up from almost zero a year ago. DIY would have previously been a category relegated to amateur enthusiasts, but the context of their growth here is in the area of “operational theatres”, Dedrone notes.

Interestingly, you can see that there is a smaller category of “other” that is also on the rise: these will include a large number of startups that are building their own equipment, potentially on the back of millions, tens, or hundreds of millions of dollars in funding. Collectively, these are now accounting for 2.5% of all drones in the sky, with no single vendor large enough yet to break out.

Put another way, Dedrone notes that DJI flight counts across the region and year decreased by 21.8% while DIY counts went up by more than 213%.

“This shift toward diversity indicates the fast pace of evolution of drone threats as

pilots expand their horizons to other, harder to detect, platforms,” Dedrone writes.

The cost differential is staggering.

One lesson Ukraine is most definitely driving home is that biggest isn’t always the best. Whether it’s a put-together DIY effort from a group of clever technologist makers, or a device by a named producer, drones are drastically undercutting traditional equipment when it comes to cost, procurement times and iteration cycles.

And in the most pointed scenarios, the smaller devices can prove lethal to the biggest. Dedrone highlights one high-profile claim that an F-35 fighter jet (cost: more than $82 million not including fuel and other running costs) could be intercepted by a drone costing less than $500.

“If defenders fail to match this pace, the skies will belong to the most agile, not the most powerful,” Dedrone writes.

There are also efforts underway to better equip those F-35s with their own drone power as a defence.

Detection is increasingly elusive.

Tracking drones has become a moving target of its own, Dedrone notes.

Part of the reason for this is because drones have been built to bypass the tools that were traditionally used to track air, ground and water vehicles — as Dedrone describes it, equipment was used to track the communications that those vehicles emitted, “steady radio emissions, and radar signatures large enough to stand out from background clutter.”

That has led to a chess game involving building more sophisticated radio frequency use, leading to better detection, leading to better evasion, and so on.

In 2025, more than 80% of the drones detected by Dedrone in the region were found using RF systems.

But Dedrone notes that it’s now seeing more “RF-silent” flights with no signal emissions at all. Instead, launchers are releasing drones using a variety of other technologies and strategies to evade any kind of tracking by traditional means. These include releasing drones in swarms, sometimes from a “mothership” drone. that communicate with each other, using GPS and AI to move to their targets. They are also leaning into Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM), LiDAR use, on-drone inertial navigation systems, visual odometry, and fibre-optic tethers “that bypass jamming entirely.” The swarms can be made up of as many as 10,000 drones, effectively using mass-scale to jam detection efforts.

“An RF-silent drone does not just evade one sensor, it can create a blind spot across an entire defense network,” Dedrone writes. “The fight is no longer just to spot drones, but to anticipate new configurations before they appear. Without that shift in mindset, defenses will remain one step behind attackers who can change shape overnight.”

The rising tide for nautical drones.

There have been some notable developments in the UK and Europe that should lead to more advances and a wider array of uncrewed nautical craft that will be used for reconnaissance but also “maritime disruption” and outright attacks. Dedrone identifies this as an area to watch. Specifically, the seas represent a new frontier, with nautical uncrewed or autonomous vehicles “exploiting blind spots in traditional radar and sonar coverage for blind spots when it comes to detection.”