After decades of being out of bounds for most European VCs, defence tech is in the frame. This year appears to be a pivotal one for the resilience tech funding ecosystem.

In May, the European Investment Fund (EIF) — an LP in many if not most European venture funds — committed €40 million to the “defence, security, and space” fund by Keen Venture Partners, a firm based in Amsterdam. EIF’s participation was notable because it was its first time it had backed a fund solely focused on military (rather than dual-use, or no-military use) technologies.

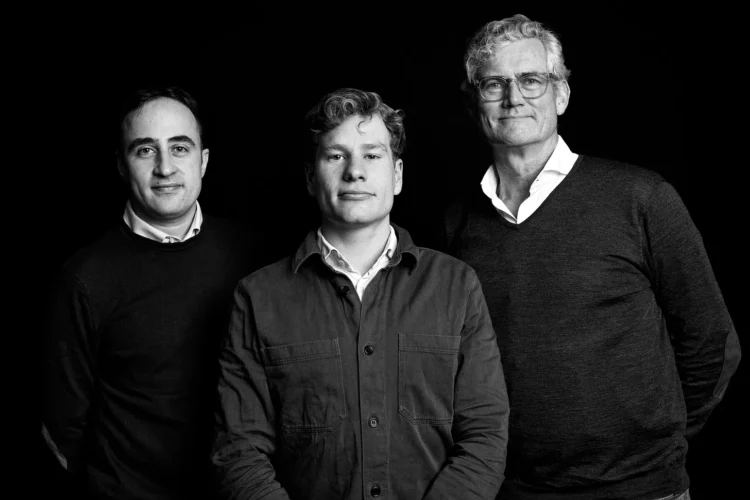

“We are here to invest in technology that serves the purpose of the Ministry of Defence or the Ministry of Internal Affairs, directly or indirectly,” the fund’s partner Giuseppe Lacerenza told Resilience Media.

To fulfil its mission, Keen plans to work closely with MoDs across Europe. Lacerenza, who is himself a military school alum, said Italy and the Netherlands are examples of countries where the firm has been able to establish close connections. The fund has also formed an advisory board that includes former Dutch minister of defence Kajsa Ollongren and Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, former secretary general of NATO, among others.

“We are also extremely collaborative and we see a world where we co-invest […] with other funds that may fill our gaps,” Lacerenza said. “ Because in the end, investing in those relationships [with MoDs] takes a lot of time.”