The consumerisation trend in enterprise IT has an analogue in defence tech: hardware and software products originally built for commercial markets are now getting adopted and adapted by startups building the next generation of munitions and more for military use.

In the latest development on that front, Firehawk — a US-based startup that has figured out a way to use off-the-shelf 3D technology to produce rocket propellant and artillery charges at a lower cost and with a faster turnaround than traditional methods — has closed out its Series C of over $60 million, after picking up a new strategic investor and partner out of Europe.

Presto Tech Horizons, a partnership between Prague-based Presto Ventures and the Czech defence contractor/ammunition specialist CSG, is making the investment, which values Firehawk at $290 million post-money.

The exact amount PTH is investing is not being disclosed, but the startup confirmed to Resilience Media that the latest equity injection closes out the company’s Series C, which was initially announced earlier this year and led by 1789 Capital, the investment firm where Donald Trump, Jr is a partner. Other backers in this round include Draper Associates, Decisive Point, Stellar Ventures.

Overall, Firehawk has around 30 investors on its cap table, per data from PitchBook. RTX and Cathexis are among its other strategic backers. Arguably, having a firm where the son of the President of the United States is a partner may well also be strategic on another level.

For the record, Will Edwards, Firehawk’s CEO and founder, said that 1789’s investment preceded Trump joining the firm as a partner, and he’s had no contact with him.

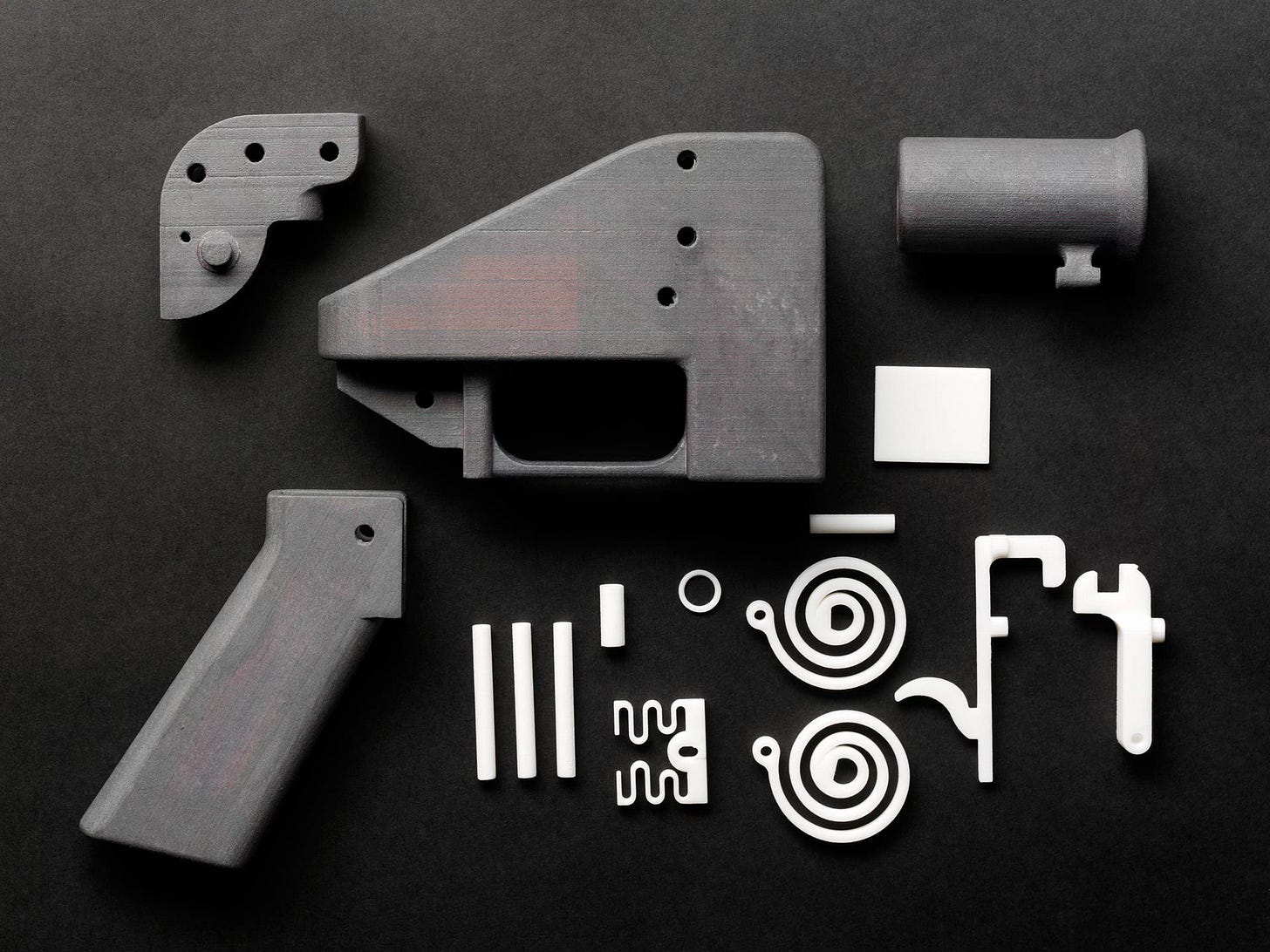

Using 3D printing in the making of weaponry is not a new concept. More than a decade ago, as 3D printers were taking off amidst a maker movement in hardware, people started formulating and distributing online blueprints for using those printers to make guns.

Startups in the US like Defense Distributed caused a huge furore testing the limits of the Second Amendment, as well as the patience of gun control advocates, over whether such designs were legal. (Fascinatingly, that work landed Defense Distributed into the hallowed halls of the Museum of Modern Art and the Victoria & Albert Museum, among others.)

The focus of Firehawk’s work is munitions, and specifically rocket propellant and artillery charges, which up to now have been tricky and expensive to manufacture with any agility because of the steps required to do so.

“It’s like the world’s most intense baking process,” Edwards said in an interview. That recipe, so to speak, involves using a giant planetary mixer where a mix of chemicals are poured and mixed for several hours, he said. The resulting propellant is then poured into moulds, which are then put into industrial ovens to cure and then a final X-Ray process to ensure they’ve set correctly. The whole process can be anywhere between 15 to 60 days, Edwards said.

Firehawk’s breakthrough is to bring all of that down to just six hours, he claims.

The company has devised a feedstock that Edwards described as “energetic”. The material gets the same performance levels, he said, but it comes out in little pellets instead of a sludge, with no shelf life to it, which can in turn be quickly turned into the required fuel. He likens it to the pre-made cookie dough sold in supermarkets: if you want to make two cookies, he said, you don’t need to buy and mix “ingredients for 30 cookies” anymore.

I don’t know how many people make just two cookies, and similarly question how many would-be customers would buy or use jet fuel in such small amounts, but when you consider how war is being waged in Ukraine, at times at a grass-roots level of combat on the part of the Ukrainians, you can understand how the military must start to think in more agile and incremental ways for the next generation of combat.

Edwards said the round is going towards the company’s development in the US as well as to build out growing momentum in Europe, where the war in Ukraine has focused countries and alliances like NATO on rebuilding their defences in the face of new geopolitical threats.

Primary customers right now are government bodies — most recently announced is a multi-million dollar deal with the US Air Force — but it’s yet to start filling out orders.

“We’re stacking our contracts so that we’re ready for low-rate production by the end of next year,” Edwards said. The idea is that with production ramping up, it will start working with larger suppliers of munitions, such as CSG, to fulfil contracts in different markets.

‘From a 10-day dangerous process to three-ish hours’

There is indeed a major push in the form of demand. Last year, it emerged that the EU was falling well short on the 155 calibre artillery shells that it had projected it would be able to manufacture to supply to Ukraine to help in its defence against Russia. One of the key components to the 155 shell is the base bleed motor, a fuel cell that helps to extend its range. This is one of the items that Firehawk can produce using its 3D process.

Edwards — disarmingly natural in his demeanour considering he’s talking about making weapons to increase lethality — said the 155 shell shortfall right now is “one of the really neat opportunities” ahead of Firehawk. “We’ve cut that production from about a 10-day relatively dangerous process to three-ish hours.”

In the US, he said the company is building out a lot of manufacturing and testing facilities. They include 42,000 square feet in the Dallas area where it is headquartered; a 30-square mile launch range in western Texas; 20 acres elsewhere in the state for building engines; and a 300-acre parcel near Fort Sill in Oklahoma where it is building a full production facility.

European efforts, given its new investor, might likely come by way of partnerships with local providers.

“The current geopolitical situation underscores the need to invest in innovative defense technologies,” said Michal Strnad, chairman of the board and owner of CSG, in a statement. “Firehawk can play a crucial role in the future of not only rocket propulsion, but also ammunition production. This innovative project can strengthen cooperation between leaders of the American and European defence industries.”

There will continue to be lots of other challenges to making the full production of munitions more agile. One of those roadblocks, it seems, is no longer startups getting funding.

Edwards noted that when Firehawk first started in 2019, he knocked on doors from the East Coast to the West Coast, but it was impossible to raise money. Things changed after two developments. The first was Firehawk’s move to Texas from the East Coast (it was started in his apartment in the Washington DC area and then moved to Florida), which put them in the heartland of the defence industry in the country. The second was the war in Ukraine, he said, and the message that it sent to the industry about modernising.

What Firehawk has built so far speaks to the bigger opportunity here not just to “disrupt” defence, but to do so by tapping into products that have already been built for a very different audience, in this case 3D design enthusiasts.

“To be able to print [fuel propellant] off a commercial off the shelf printer, printing whatever you need, that’s really the innovation,” he said. “And we’ve never blown up a printer.”

(They test all the time, he added, and will continue to do so.)