Skana wants to shore up coastal defence with amphibious vessel for shallow waters

The Alligator is built for that littoral 'grey zone'

In a year when the Baltic has turned into a geopolitical house of mirrors, with Russian “shadow fleet” tankers slipping through NATO waters under borrowed names and false identities, the issue of maritime security is firmly in the spotlight.

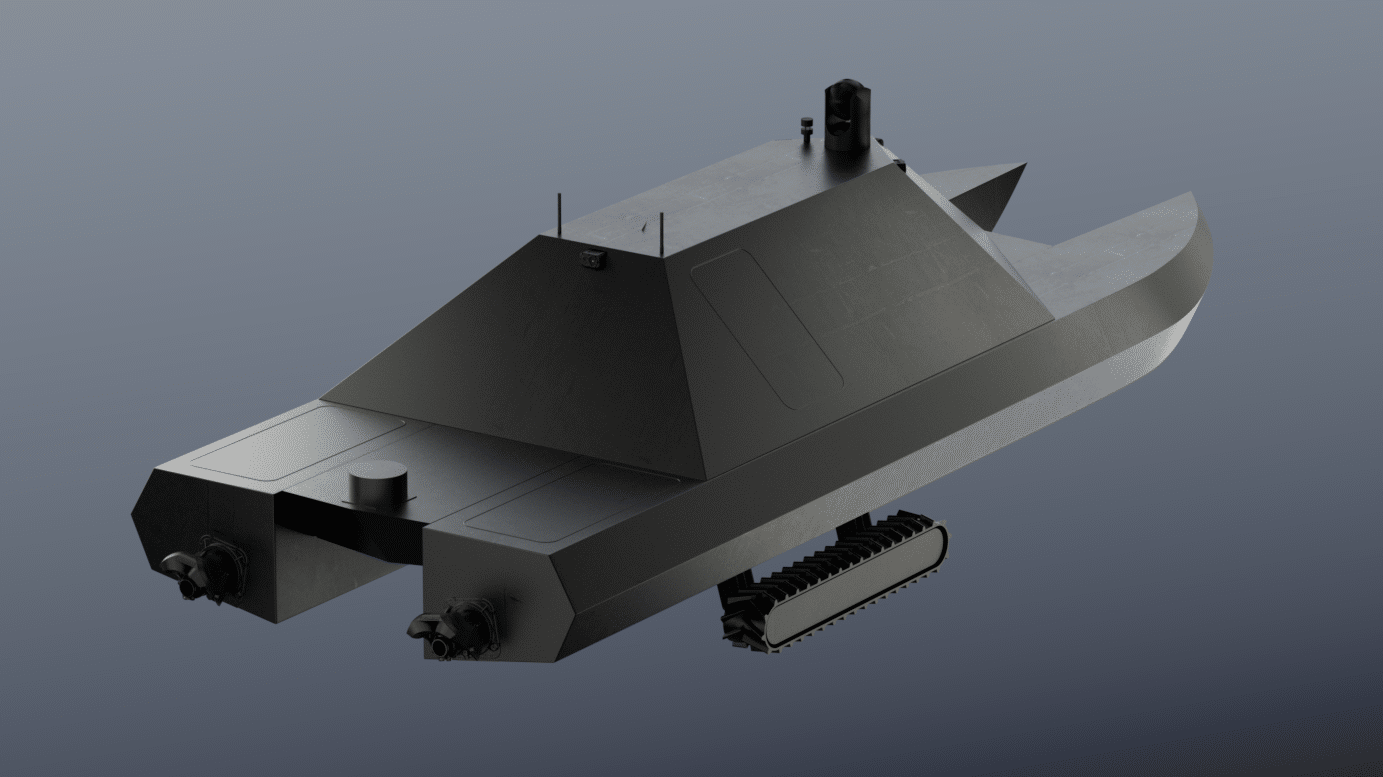

With that spotlight widening, Skana Robotics, a Tel Aviv defense startup built by naval special-ops veterans and robotics engineers, thinks it has an answer with something that looks more machine than ship: the Alligator, an amphibious vessel that needs no dock, can operate manned or unmanned, and serves as a mobile launchpad for other autonomous systems.

Recently, coastlines and key passageways across Europe have shown how quickly the maritime picture can unravel. The Red Sea has seen commercial shipping disrupted by missile and drone attacks; the Black Sea has endured strikes on ports and coastal infrastructure; and Europe has faced unexplained damage to subsea cables and pipelines. Each incident has exposed a recurring blind spot in how maritime forces respond to fast-moving crises in shallow, congested, or hard-to-access coastal waters — a blind spot that existing systems were never designed to cover.

“Recent events in the Red Sea, the Black Sea, and around damaged subsea infrastructure in Europe highlight this gap clearly: responses are either too slow because access is limited, or too risky because only high-value manned vessels can reach the area,” Skana co-founder and CEO Idan Levy told Resilience Media. “The Alligator is built precisely for that grey zone — where speed, amphibious access, and the ability to operate without infrastructure decide the outcome.”

Built for the in-between

Unlike traditional naval craft, the Alligator can drive itself into the sea. No dock, no crane, no choreography. It can move across beaches, debris, and broken shorelines before transitioning straight into the water.

“It’s built to handle the messy, real-world littoral zone [the near-shore area] — not just clean ramps and perfect beaches,” Levy said.

And once it’s underway, the vessel manages the routine adjustments on its own under what Levy refers to as “supervised autonomy mode,” where the system handles the immediate, time-sensitive navigation tasks while the human remains responsible for the larger intent.

“The human defines the mission goals and constraints and stays firmly in the loop for intent, rules of engagement, and any use of effectors,” Levy said. “The vessel’s autonomy is there to handle complexity and time-critical adjustments, not to replace human judgment.”

So what, exactly, is the Alligator? It’s not a boat, not a landing craft, and not a USV (unmanned surface vessel) in the usual sense. Skana prefers a different label.

“We think of Alligator as a Littoral Autonomous Amphibious Tender rather than a classic hull type [traditional vessel category],” Levy said. “It’s not just a landing craft that happens to be unmanned, and it’s not a pure USV that lives only in the water — it’s a platform designed to bridge land, surf zone, and subsea in one continuous mission thread.”

Conceptually, that makes it an amphibious utility vehicle for hauling supplies, supporting underwater drones, and handling security tasks in the messy zone where land and sea overlap.

In practical terms, the Alligator is a compact 10.5-metre amphibious craft with a 3-metre beam and a shallow 0.4-metre draft. It carries up to 1,500 kg of payload, has a range of 300 nautical miles, and can reach 35 knots at sea while crawling at about 5 km/h on land. Propulsion comes from twin waterjets supported by a hydraulic drive system for ground movement, with a modular payload bay designed to carry supplies, sensors, or autonomous underwater vehicles.

For anyone wondering how a human would actually ride such a low-profile machine, Skana says the upcoming version shown publicly is the uncrewed model. A separate, fully manned configuration — with a dedicated crew layout — is already in development and will be unveiled as part of the broader Alligator family.

A shore thing

Founded in 2023, Skana has raised about $4.3 million in pre-seed funding to date, according to Levy, with plans to announce a larger seed round in early 2026 — around the same time the Alligator is expected to move from prototype into production and join the company’s operational lineup.

This lineup includes a duo of autonomous vessels unveiled a few months back: the Bullshark, a surface drone for patrol and sensing, and the Stingray, an underwater drone for stealthy reconnaissance, both now in early trials with operational partners globally.

Under the hood, the Skana fleet runs on two layers of software. SeaSphere is the operational brain — the centralized system that plans missions, assigns roles across the fleet, and sets the autonomous behaviors each vessel should follow. Vera is the “programmable command core”: the part that executes those instructions locally, adjusting speed, course, and teaming behavior on the fly as conditions shift.

In the mission interface, that can show up as multiple vessels — Bullsharks, Stingrays, and Alligators, which update their status and movement in real time.

What ties it all together is the orchestration. SeaSphere sets the plan by deciding which asset should patrol, dive, scout, or carry a payload, while Vera handles the execution on each machine, adjusting to the environment. So in practice, this means a Bullshark on the surface, a Stingray below, and an Alligator at the shoreline can operate as a single system, sharing tasks and reacting to the same mission picture instead of behaving like three disconnected drones.

If this sounds a little like swarm control, which refers to a mass of identical units moving in concert, you’d be mistaken.

“Most so-called ‘swarm’ technologies focus on controlling large numbers of identical unmanned assets,” Levy explained. “Navies, in contrast, operate heterogeneous, hybrid fleets made up of manned ships, unmanned surface vessels, underwater vehicles, aircraft, and fixed infrastructure — and until now, there has been no unified operational brain that can plan, simulate, and allocate resources coherently across all of these layers.”

So in effect, SeaSphere is positioned as that “missing layer” – a single, unified system that allows navies to simulate missions, plan operations, and allocate resources across hybrid fleets dynamically.

“That alone is a game changer,” Levy continued. “Instead of fragmented control systems and stovepiped planning tools, commanders finally see and manage the entire operational picture as one system.”

Zooming out, the pitch is perhaps less about an amphibious, autonomous fleet, than it is about a different way of thinking about maritime presence. Instead of relying on one or two high-value ships to cover everything, Skana imagines dozens of low-signature platforms patrolling coastlines, launching underwater drones, and complicating any adversary’s grey-zone activity. In effect, a shift from concentrated power to distributed networks.

“You may not match a major power in tonnage, but you can create a persistent, affordable web of sensing and effects that still delivers real deterrence,” Levy added.